Dev Blog

| ./dev |

|

Original theme by orderedlist (CC-BY-SA)

Where applicable, all content is licensed under a CC-BY-SA.

|

Fisher-Yates Shuffle

The Fisher-Yates shuffle algorithm is used to create a random permutation. The derivation is relatively straight forward:

function fisher_yates_shuffle(a) {

var t, n = a.length;

for (var i=0; i<(n-1); i++) {

var idx = i + Math.floor(Math.random()*(n-i));

t = a[i];

a[i] = a[idx];

a[idx] = t;

}

}

We choose the first element at random, then proceed to choose subsequent entries from the remaining elements.

As a spot check, we can confirm that there are $n!$ configurations yielding approximately $ n (lg(n) - 1) $ bits of entropy. Each poll of the random number generator is for $ lg(n-i) $ bits over $n-1$ entries:

$$ lg(2) + lg(3) + \cdots + lg(n) = \sum_{k=1}^{n} lg(k) = lg(n!) $$

The Wrong Way

One can consider the following incorrect way to do the shuffle:

function nofish_shuffle(a) {

var t, n = a.length;

for (var i=0; i<n; i++) {

var idx = Math.floor(Math.random()*n);

t = a[i];

a[i] = a[idx];

a[idx] = t;

}

}

a slight variant:

function noyaks_shuffle(a) {

var t, n = a.length;

for (var i=0; i<n; i++) {

var idx = Math.floor(Math.random()*(n-1));

if (idx==i) { idx = n-1; }

t = a[i];

a[i] = a[idx];

a[idx] = t;

}

}

and another:

function nomaar_shuffle(a) {

var t, n = a.length;

for (var i=0; i<n; i++) {

var idx0 = Math.floor(Math.random()*n);

var idx1 = Math.floor(Math.random()*n);

t = a[idx0];

a[idx0] = a[idx1];

a[idx1] = t;

}

}

Where the difference in nofish_shuffle and noyaks_shuffle is to skip the current index when considering which element to permute. nomaar_shuffle is yet another variant where each two elements are chosen at random and swapped $n$ times.

A friend of mine suggested an nice proof to show the above two shuffle algorithms provide incorrect results.

As above, there are $n!$ possible shuffles we want to choose from, with equal probability. Since nofish_shuffle is choosing each element to permute from the whole array, there are $n^n$ possible choices for the permutation, where some permutations might be represented more than once.

Producing multiple configurations is permissible so long as nofish_shuffle would produce an equal distribution for each of the $n!$ configurations. Since $ n! \nmid n^n $ for $n>2$, there must be some configurations that appear more often by the pigeonhole principle.

noyaks_shuffle doesn't fare much better since there are $n^{n-1}$ possible choices of permutation schedules and $n! \nmid n^{n-1}$ for $n>2$. The same type of analysis works for the nomaar_shuffle by noticing that the number of permutation schedules is $n^{2 n}$ and that still $n! \nmid n^{2 n}$.

Though hidden in such a large configuration space, nofish_shuffle, noyaks_shuffle and nomaar_shuffle produce configurations that are not uniformly distributed.

Addendum

Sattalo's algorithm creates a random single cycle permutation. The algorithm is similar to Fisher-Yates but does not allow the choice of the current index element when swapping:

function sattalo_shuffle(a) {

var t, n = a.length;

for (var i=0; i<(n-1); i++) {

var idx = i + 1 + Math.floor(Math.random()*(n-i-1));

t = a[i];

a[i] = a[idx];

a[idx] = t;

}

}

There are $(n-1)!$ configurations, so we know the above algorithm subsamples from the space of all permutation possibilities.

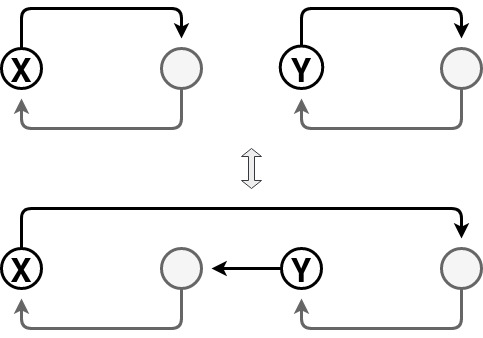

To see that it produces a single cycle, note that swapping elements has two possibilities:

- If both elements are in the same cycle, swapping elements creates two disjoint cycles

- If both elements are in different cycles, swapping elements creates a single cycle

The swap step in Sattalo's algorithm can be thought of as swapping a cycle of length one, the current index position, with another cycle pointed to by the chosen random index. Since these are two distinct cycles, they join to create a single cycle. This is done $(n-1)$ times forcing a single large cycle.

To see that this draws uniformly from single cycle permutations, proceed inductively by noticing that if a single cycle of length $(n-1)$ is produced uniformly at random, then extending it to a single cycle of length $n$ by the above method will favor each of the $(n-1)$ possible extensions equally.